| Version 7 (modified by , 12 years ago) (diff) |

|---|

Chapter 2 of Bombay Cinema: An Archive of the City by Ranjani Mazumdar

If a simmering rage drove the “angry man” and the “psychotic” in their explorations of the city, then the tapori (vagabond) speaks to a structure of feeling strongly rooted in the hybrid cultures of Bombay’s multilingual and regional diversity. Performance and performative gestures are crucial to the tapori’s agency. This performance deploys sharp street humor and an everyday street language, in addition to a deep skepticism toward power and wealth. Using the popular Bambayya language as his weapon against an unequal world, the tapori creates a space through insubordi- nation that endows him with a certain dignity in the cinematic city. Drawing attention to the self through linguistic and stylistic perfor- mances, the tapori creates a space where control is possible. Deploying an irreverent masculinity that contrasts with the dominating male pres- ence of the “angry man” era,1 the tapori stands at the intersection of morality and evil, between the legal and the illegal, between the world of those with work and those without work. Lacking a home but long- ing for a family, the tapori occupies the middle space between the crisis of urban life and the simultaneous yearning for stability. Part small-time street hood and part social conscience of the neighborhood, the tapori embodies a fragile masculinity that is narrated through a series of en- counters with the upper class and the figure of the woman. In performing and depicting marginal figures whose narrative predicaments seem to mirror their psychological states of marginality, we see a verbal and social alienation expressed in the tapori’s performance.

This alienation

42 The Rebellious Tapori

is countered through style and gesture to both shock and play with the signs of the everyday.

The tapori’s hybrid speech creates the possibility of transcending vari- ous other identities. It is important to stress this point because the Hindi film hero typically tends to be a North Indian figure. Scriptwriter Javed Akhtar sees Hindi cinema as “another state within India” that does not need to be located or defined specifically as a region (cited in Kabir, 53). He does, however, acknowledge that the “usual Hindi screen hero is a North Indian, perhaps a Delhi Haryana U.P mixture” (cited in Kabir, 53). At the same time, Akhtar reiterates that the hero is “from everywhere and from nowhere” (cited in Kabir, 54). This contradiction in Akhtar’s perception about the Bombay film hero is revealing. Whatever the dif- ferent inflections may be, Hindi cinema has by and large retained the visual, emotional, and cultural iconography of a broad-based North Indian experience. It would be difficult to try and establish this as other- wise. What I propose to show in this chapter is a “field of tension” within Bombay that provokes us to think through the image of the tapori—a figure whose performance has the potential to destabilize the “North Indianness” of the hero — as an ensemble of sounds, signs, phrases, and gestures. Performativity and style operate here to create a rebellious figure of the street. This is a formulation based on the different ways in which the tapori’s imagination has emerged out of a complex web of linguistic, spatial, and imaginary journeys. Language, the Film Industry, and the Rise of Bambayya

Popular wisdom has it that it is the film industry that has kept Hindu- stani alive. This perception exists despite the gradual “purification” of Hindi in postcolonial India, the historical origin of which can be traced to the Hindi movement of the nineteenth century.2 The film industry’s use of Hindustani, in an official climate in which the national state language was gradually becoming Sanskritized, has been a remarkable achievement. The cinema’s contribution toward ensuring the survival of Hindustani in the backdrop of an increasing linguistic warfare enabled the cinema to create space for other forms of experimentation. The location of the film industry in a non-Hindi-speaking region allowed the industry to both preserve and experiment with its spoken language. This, in turn, resulted in new kinds of performances through figures who embodied the specificity of the “Bombay experience.”

The Rebellious Tapori 43

The Bombay film industry was born in the shadow of linguistic con- flict that carried on well into the twentieth century. The silent era did not have to deal with the language issue. It was only with the birth of the talkies in 1931 that language became central to the imagination of the Bombay film industry.3 While catering to large sections of the population in North India, the industry was located in the capital city (Bombay) of a non-Hindi-speaking region (the state of Maharashtra). What is inter- esting is the decision of the film industry to use Urdu/Hindustani? as the language of Bombay cinema. This is all the more remarkable in the face of the entrenched position taken by Hindi-language elites, who advo- cated a Sanskritized rendering in opposition to Urdu.

Alok Rai suggests a rural-urban division in the language debate. The Persian stream was represented by urban Muslims, professionals, and Kayasths. The Nagari stream was more rural, but it represented a signifi- cant proportion of upper-caste Hindus, including Brahmins, Banias, and Thakurs (Rai, 255). This rural-urban split may have been decisive in the industry’s decision to favor Urdu. Urdu was the language favored by urban poets and writers, many of whom joined the film industry. The predominance of Urdu/Hindustani? in the industry is now an undisputed and acknowledged fact and can be traced to a number of reasons aside from the rural-urban split. In an interesting foray into the linguistic roots of Hindi cinema, Mukul Kesavan suggests that the melodramatic nature of the Hindi film form could best be captured through “Urdu’s ability to find sonorous words for inflated emotion” (249). Javed Akhtar traces the connection between Urdu and the film industry to the pre- cinematic urban cultural form of Urdu Parsi Theater. These theaters were owned by Parsis living in Bombay. The early Parsi theater created a certain style that combined drama, comedy, and song (Kabir, 50).

Akhtar says:

The Indian Talkie inherited its basic structure from Urdu Parsi Theatre and so the talkies started with Urdu. Even the New Theatres in Calcutta, used Urdu writers. You see, Urdu was the lingua franca of urban north- ern India before partition, and was understood by most people. And it was—and—still is—an extremely sophisticated language capable of portraying all kinds of emotion and drama. (cited in Kabir, 50) Urdu was definitely the most important language for the Hindi film industry. Urdu’s accessibility for a huge mass of the North Indian urban population made it appropriate for the film industry to adopt it. The

44 The Rebellious Tapori

presence of many writers who wrote in Urdu was the other reason for the popularity of the language in the industry.4 The use of a poetic, highly cultivated and developed language was thus accepted by the industry and by the audiences that patronized the cinema. Even when filmmakers made the effort to address the streets of the city, the characters retained this poetic language (as in the film Kismet, 1943 ). Urdu’s survival in the film industry is not only remarkable but was possible because of the in- dustry’s location. It is this very location that has allowed for significant innovations in the image of the tapori, who speaks a peculiar, hybrid Hindi called Bambayya. In a city of migrants, where new migrants meet old ones, language tends to acquire a life of its own. The context of a powerful Hindi film industry that emerged in a Marathi-speaking state has made Bombay’s relationship to language fascinating. In the image of the tapori, we see both the performativity of a hybrid city and the language of its multi- lingual rough streets. In his use of the Bambayya language, the tapori represents both the specificity of and the conflictual nature of the city. Through his linguistic performance, the tapori shifts the course of a well- defined language system. What is interesting is that the tapori’s language embodies a polyglot culture that does not fix itself within a traditional Hindi-Urdu conflict, but rather enters a space where a multilingual street culture inflected with diverse regional accents can be captured. The first film to popularize the Bambayya language was Amar Akbar Anthony (popularly known as AAA, Manmohan Desai, 1977),5 which featured Amitabh Bachchan in the role of a small-time (Christian) bootlegger.

The spoken language of Bombay cinema has over the years been con- sidered dynamic and cosmopolitan, speaking as it does to a wide audi- ence in a multilingual country like India. As stated earlier, the arrival of the talkies first put pressure on the film industry to evolve a language (Hindi) for a wide audience. Amrit Ganghar says:

The question to be resolved was: what kind of Hindi? Sanskritized? Persianized? Or low-brow Hindi? In the event the cinema developed a Bazaar Hindi of its own called Bambayya, which is widely understood throughout the country. (233) The reference to the Bambayya language here seems a little out of place. In the early years, the film industry used a cultivated Urdu. Bambayya as a language inflected with the resonance of multiple tongues was clearly

The Rebellious Tapori 45

identified with the Bombay streets. It was used neither by the elite nor by the middle class. The bulk of the people who used this language be- longed to the working classes. It was not a language that could be easily heard in cinema. Sometimes comedians and other peripheral figures would use this language (for example, Johny Walker as Abdul Sattar in Pyasa, 1957); the hero, however, continued to speak the more “civilized” Hindustani.

In films made prior to the 1970s, the presence of migration from rural India into the city was marked explicitly by dress codes and speech. Depictions of rural presence in urban life had to rely on the use of dialects like Brajbhasha and Avadhi, which not only marked the figure as a rural migrant in the city, but also metaphorically presented “rurality” as the imagination of the street (for example, in the films Ram Aur Shyam, 1967, and Don, 1978). Rural dialects could be contrasted with the more cultivated and sophisticated Hindustani. The everyday space of the street was therefore clearly seen as the imagined space of the village. In Raj Kapoor’s Shri 420 (1955), the song “Ramayya Vasta Vayya” generates an imagined universe of the village as a counterspace to the harshness of the city. The community of rural people singing collectively represents the “good city” as they invite the protagonist Raj to join them and identify with their communitarian spirit. The tapori is, however, marked as an ordinary man of Bombay whose language emerges out of a polyglot city- street culture that is entirely urban. The lack of sophistication and street speech is not introduced through village dialects as in earlier films, but through a combination of English, Gujarati, Marathi, Hindi, Tamil, and various other linguistic resonances. While retaining an overall Hindustani speech, the tapori’s linguistic turns and phrases evoke a new imagina- tion of the street, wherein the urban identity of a multilingual Bombay street culture gets constituted and reinfused with cinematic iconicity.

It is difficult to trace how the Bambayya language actually emerged. Scriptwriter Sanjay Chel, who coauthored the script for Rangeela, offers an explanation based on a sense of the street and the nature of Bom- bay’s hybridity. Chel says: People come here from all over India with their languages like Gujarati, Marathi, Bengali. All these languages merge to form a unique language of survival in the city, to stubbornly fight for existence in the city. This language is understood by all. This is a language of the street with its own texture. It may not be grammatical, but this Bambayya language

46 The Rebellious Tapori

is hard hitting and satirical. (interviewed in Mazumdar and Jhingan, “The Tapori as Street Rebel”)

Chel’s assertion about Bambayya’s ability to contest the power of a uni- tary language, drawing on the experiences of the city, has interesting possibilities. Mikhail Bakhtin has argued that language is densely saturated with the concrete experiences of history. Language is a contested site, a space within which “differently oriented social accents as diverse ‘sociolinguistic consciousness’ fight it out on the terrain of language” (Stam, 8). Since language exists within an unequal regime of power, its uni-accentual drive is constantly challenged by the multiaccentual presence of the oppressed. Language is deeply implicated in a politics of the everyday, whereby it becomes imperative to recognize the different ways in which “Politics and language intersect in the form of attitudes, of talking down to or looking up to, of patronizing, respecting, ignoring, support- ing, misinterpreting” (Stam, 9). Clearly, attitudes, expressions, and ges- tures have a unique relationship to language. It is in this combined ter- rain that power is both constituted and challenged.

Like Bakhtin, Michel de Certeau invokes the image of the “ordinary man” as a figure through whom the “vanity” of writing encounters the “vulgarity” of language (1988, 2). Both Bakhtin and de Certeau are inter- ested in the tensions that enable the anonymous figure or ordinary man the possibility of dislodging the vanity of elite linguistic formations. In aural terms, this tension becomes striking when one deals with the spo- ken language of ordinary people in a communicative and visual medium like the cinema. The tapori is the cinematic figure whose language defies the pure and moral absolutism of other heroes. Emerging in a city that is crisscrossed not only by the differences of class and caste but also by that of region and language, the tapori’s Bambayya speech becomes a nonlanguage, defying linguistic purity through a performatively charged acknowledgment of the everyday.6 To trace the specifically local dimen- sion of the image, we need to understand the cultural imagination of the “Bombay experience.”

The “Bombay Experience” and the Street

Writers, architects, and poets have tried to represent Bombay’s diversity and its brutal contrasts in imaginative ways. The most persistent image

The Rebellious Tapori 47

of Bombay is the cheek-by-jowl coexistence of skyscrapers and slums, each inhabiting a different experience and world (Kudchedkar, 127). Bombay exists “in one long line of array, as if on parade before the spec- tator” (Evenson, 168). Roshan Shahani looks at the representation of Bombay in the fiction of many writers to suggest the textual evolution of a multifaceted Bombay. Says Shahani, “to locate the narrative text in Bombay, is to textualize the complexity of its realities and to problematize the unrepresentative quality of a ‘typical’ Bombay Experience” (105). Bombay emerges here as an “imagined topos,” a fictionalized landscape of history and experience wherein the city’s diversity, contradictions, and paradoxes “defy any easy definition” (Shahani, 105). Bombay is also a city that showcases the world of glamour and glitter — a “seductive trap that seems to offer much to the upward bound but actually gives very little” (Alice Thorner, xxiii). At one level, the city appears like a “three- dimensional palimpsest” articulating the ambitious drives of a succes- sion of builders; at another level, it presents the city as a sea of slums belonging to the endless migrants in the city.

This narrative of contrasts and compressed spaces has been central to the way Bombay has been imagined in literature and cinema and has informed the city’s cultural imagination throughout the twentieth cen- tury. The portrayal of Bombay’s affluence is exaggerated to highlight its darker and uglier side. For poet Nissim Ezekeil, Bombay “flowers into slums and skyscrapers” (cited in Patel and Thorner 1995, xix). For Marathi poet Patte Bapurao, the city appears like a stage of oppositions, such as the Taj Mahal Hotel and the workers’ chawls,7 speeding modern cars and helpless pedestrians (cited in Alice Thorner, xix). The popular song “Ye Hai Bombay Meri Jaan” (This is Bombay, my love) from the film CID (Raj Khosla, 1956) evokes a phenomenology of the city in which, in the midst of buildings, trains, factory mills, and the ubiquitous crowd, there exists a subculture of gambling, crime, and claustrophobia. This is a space purged of humanity; the crowd moves mercilessly, pushing aside those who cannot keep up with its pace. This diversity and plurality of experience, language, and class produces an acute sense of the city’s hybridity. To this, one can now add the rapid proliferation of high-tech products, visual images, and the simultaneous aestheticization and decline of the streets.

Yet brutal contrasts combined with hope have also fueled the creative imagination. Referring to Sudhir Mishra’s film Dharavi, Amrit Ganghar

48 The Rebellious Tapori

suggests that the film’s objective is to capture the individual dreams of its inhabitants: Each individual has a dream of making it rich: a dream fuelled both by the glitz and affluence of actual upperclass life in Bombay, and by popular cinematic fantasies in masala movies. (214)

Bombay has been described by Gillian Tidal as “a mecca for incoming peoples, seeking work, seeking money, seeking life itself ” (cited in Con- lon, 91). Scriptwriter Khwaja Ahmad Abbas imagined Bombay as the space for constant struggle and hope: Some tens of thousands come here to make their future. Some make it, others don’t. But the struggle goes on. That struggle is called Bombay. The struggle, the vitality, the hope, the aspiration to be something, anything, is called Bombay. (165) In a recent essay, Gyan Prakash captures the lure of the dream city as something that has traveled through signs, gestures, and images. The de- sire to experience the offerings of the city circulates outside of Bombay, contributing profoundly to the creation of an imaginary city (Prakash 2006).

Bombay is also part of a global chain like no other city in India. This is amplified in the visuals and sounds that circulate through the city. The circulation of an intertextual network of visual and aural signs makes contemporary urban landscapes into “culturescapes” (Olalquiaga). In the “culturescape,” temporal movement is represented in a pastiche com- bination of the here and the now, the past and the future, the global and the local. This supposedly nonrational configuration within the “culture- scape” points to the city’s inability to cater to the requirements of its growing population. Though not about Bombay, Olalquiaga’s descrip- tion is a dynamic aspect of urban life, a chaotic city, its hybridity visible in all aspects of life, its dreams circulating within the “ruins of moder- nity.” This hybridity can be neither romanticized nor rejected, for it cre- ates a uniquely specific topography. To wander in the streets of this diverse city as a “have-not”, and yet retain a sense of identity and be- longing is to create an imagined landscape of resistance. The space of this resistance belongs to the cinematic tapori.

Writing on the culture of cities, Henri Lefebvre made a distinction between the different levels and dimensions that go into the reading of a city. The buzz of what actually takes place in the streets and squares con-

The Rebellious Tapori 49

stitutes the “utterance” of the city. The language of the city, on the other hand, is made of “particularities specific to each city, which are expressed in discourses, gestures, clothing, in the inhabitants” (1996, 115). Seen in this context, the tapori is the cinematic articulation of a “Bombay expe- rience” whose body operates like a text that lends itself to multiple pur- poses. Sliding from ordinary humor to everyday resistance, the tapori emerges as a rebel who represents the vibrant “culturescape” of the street. The historical importance of the street in Hindi cinema was dis- cussed in chapter 1. The changing function of the street alludes to differ- ent kinds of representational possibilities. In the post-independence period the street in cinema became an extension of the nation because it was the space that could transcend the regional boundaries that actu- ally divided different parts of the country. Madan Gopal Singh offers an interesting connection between the street and homelessness:

Immediately after Independence, if we look at the popular forms of address, we have Chacha, we have Bapu, we have Sardar. So the idea of nation as extended family is very clearly entrenched. The street is seen as an extension also of home and to the extent the person involved is actually celebrating the state of homelessness in a new order, where he is on one hand part of an extended family, on the other hand there is no specificity of space where he can be located. I think that paradox is very interesting. We are in the process of discovering where we would be at that time. This is a recurring theme in popular cinema in the 1950’s and Awara is a seminal film. (interviewed in Mazumdar and Jhingan, “Tapori as Street Rebel”)

Abstracted from location and specificity, the street in Awara (Raj Kapoor, 1951) is invested with the power to locate and address anybody in the nation. The well-known 1950s song “Awara Hoon” from Awara shows Raj Kapoor (who acted in, as well as directed, the film) walking down a street singing. The location of the street is not specified as the song invokes a universe of images, transcending into an imagined space of the “national.” During the decade of the 1950s, cinema deployed differ- ent methods and metaphors to condense the nation in its images; the use of the street in Awara is clear evidence of that.8 In the tapori films (Rangeela, 1995; Ghulam, 1998), the metaphor of the “street” as “nation” transforms into the “street” as Bombay. The modern tapori emerges from the maze of Bombay’s streets using a unique language and gestures wherein performance becomes his sole identity.

50 The Rebellious Tapori

In an evocative look at Bombay through the eyes of a wandering passerby, Marathi poet Narayan Surve writes: We wander in your streets, squares and Bazaars; Sometimes as citizens, householders at times as loafers These streets carry the festival of lights into the heart of the night; Balancing two separate worlds with all their splendor These crowds move ahead but where? A traveler amongst them I too move, but where? (cited in Kudchedkar, 149) The “loafer” in Surve’s poem sees the magical, seductive appeal of neon lights and rich neighborhoods set against the expanse of slums. While desiring the pleasures of this elite world, the “loafer” rejects its authority, power, and hierarchy—these are the qualities of the cinematic tapori. The city may present itself as a glitzy, panoramic, seductive place, but for the ordinary man in the street, the panorama is a fiction. The walkers/ pedestrians in the street are people whose “bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban ‘text’, they write without being able to read it” (de Certeau 1988, 93). These men pick up fragments from the sea of signifiers available to them in order to create their own stories. As the rebellious urban figure/body in the street, the tapori is a visual ensem- ble of floating gestures, movements, and expressions, both cinematic and non-cinematic.

Cinematic Intertextuality and Performance

The creation of the tapori brought together many character types from both national and international cinema. There is a peculiar hybridity in the performance, the dress codes, and the character’s intentionality, which suggests that the tapori exists as a layered articulation of different character types. In a reflexive gesture, director Ram Gopal Varma9 alludes to this cinematic creation in his title sequence of Rangeela. Images of well-known film stars are placed alongside the credit track, combined with a sound track of chaotic city traffic. What we witness is a brief his- tory of the iconic figures of Bombay cinema. The nature of the sound

The Rebellious Tapori 51

track reveals an effort to make connections between the image and the city. The film’s opening is significant in its evocation of a cinematic world within the city. We are invited to participate and engage with another city icon of the cinema—the tapori. The tapori emerged, like the “city boys” of Hollywood cinema, from the confluence of “performance, genre and ideology transmuted into popular entertainment.” (Sklar, xii). Robert Sklar’s exhaustive study of three actors (Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, and John Garfield) pre- sents them as characters who represented “the teeming ethnic polyglot of the modern industrial city—especially New York” (xii). There are popular references to Bombay as the “New York of India,” which make the analogy with the tapori relevant. Film director Aziz Mirza describes the tapori as a highly urban phenomenon whose combined projection of cynicism and innocence makes the character attractive to audiences, thereby leading to the tapori’s emergence as an established figure in recent years.

Mirza says: The term tapori by itself is urban and tapori is a character you can only get in Bombay beacause the very nature of the city, its cosmopolitanism makes the tapori use a language of his own, which is very Bambayya. Bombay is the only city besides New York, where you can get so many people of different cultures, different races from all areas of India who live together. So Bombay has developed a language of its own and the tapori is street smart. (interviewed in Mazumdar and Jhingan, “The Tapori as Street Rebel,” 1998) The polyglot culture of New York City obviously resembles the multi- lingual diversity of Bombay. The intertextual current of signs can be seen in other visual characteristics of the tapori: the swagger; the attitude; the use of leather jackets, boots, jeans, and bikes; the leaning posture against the wall; and the forms of greeting in the street. These “bor- rowed” signs evoke the sensibility of many famous Hollywood rebel-male figures. Three well-known Hollywood actors — Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando, and James Dean — have been described as “rebel males . . . torn between traditional and novel images of masculinity” (McCann?, 28). The rebel male is seen as a figure whose “body is not unhinged from the mind as in the brute, it is the expression of self-hood, of the ability to originate ones actions” (28). Further “It is the democratic equivalent of Baudelaire’s dandy/flâneur.10 Its guiding myth is the myth of youth itself ” (28).

52 The Rebellious Tapori

The tapori most certainly appears like the democratic equivalent of Baudelaire’s dandy. He shuns class, but desires and knows the elite world. Moving through spectacular city spaces and the city’s seamy underside, the tapori’s gaze is not that of distraction (a privilege of the dandy). Rather, the tapori masters his gaze to retain and assert his power and performative agency. Scriptwriter Sanjay Chel draws attention to this gaze of the tapori within the context of a new culture of globalization, wherein the experience of facing the humiliating aspects of inequality makes the returned gaze a defiant one: In the 1990s after liberalization, new desires have arisen for this whole group of people. With the entry of multinationals, we see neon lights, parlors selling ice cream for 100 rupees. There are many in the city who sometimes cannot afford even a bus ticket. This social difference is a very real and felt experience for many and results in anger. This anger is displayed in their language and gesture, in the comments they make: “Kya Bare Log.” They cannot change the system; they can only laugh it off. (interviewed in Mazumdar and Jhingan, “The Tapori as Street Rebel,” 1998)

Chel is referring to a ubiquitous group of people in the city, urban young men on the margins of the “good life” who find a place in the image of the tapori, whose performative stance helps negotiate the alien- ation of urban life. The intertextuality evident in the uninhibited ap- propriation of cinematic signs popularized by Hollywood makes the tapori’s performative iconography particularly striking. To counter the powerful lifestyle myth of the city, the male body acquires a new iden- tity through a rebellious gaze and performance that is both humorous and hard-hitting. If the city is a theater of seamless narratives, then de Certeau has most vividly captured the conflict between the spectacular and the mundane: Advertising, for example multiplies the myths of our desires and our memories by recounting them with the vocabulary of objects of con- sumption. It unfurls through the streets and the underground of the subway, the interminable discourses of our epics. Its posters open up dreamscapes in the walls. Perhaps never has one society benefited from as rich a mythology. But the city is the stage for a war of narratives, as the Greek city was the arena for a war among gods. For us, the grand narratives from television or advertising stamp out or atomize the small narratives of streets or neighborhoods. (1998, 143)

The Rebellious Tapori 53

De Certeau’s narrative on the city is echoed in Chel’s perceptions about transformations in Bombay. If the city unfolds as an “empire of signs,” then how do we understand the presence of counternarratives or “small narratives” that emerge from the same streets on which the world of consumption unfolds as both a seductive and an alienating experience? In the performance of the tapori, there exists a counternarrative to the lifestyle myth of the city. The tapori’s counternarrative, unlike that of the “angry man” or other urban vigilante heroes, is playful. His style is individual and his resistance relies on an ambiguous relationship to issues of lifestyle and consumption. It is this ambivalence that enables such an interesting performance, “a space within which youth can play with itself, a space in which youth can construct its own identities, untouched by the soiled and compromised imaginaries of the parent culture” (Hebdige 1997, 401). Performance here is located within the performative space of the cinema. As copied, mimicked, or circulating gestures and style cohere around the figure of the tapori, the essential self of the character on-screen is dislodged to present the body as a site where gestures turn into allusions. Dick Hebdige writes that the posture of youth in subcultures is “auto-erotic, the self becomes the fetish” (1997, 401). This reference to the self is narrated primarily through performa- tive gesture and symbol. The gaze or defiant look, the gestures, and the tapori’s overall performativity also recall de Certeau’s observation that “gestures are the true archives of the city”(1998, 141). Within the land- scape of the cinematic city, the tapori’s performance becomes the key to understanding the specificity of the “Bombay experience” and to draw- ing attention to the idea of performance within performance. While there are many well-known tapori films, Ram Gopal Varma’s Rangeela and Vikram Bhatt’s Ghulam are two films that present us with vivid portraits of Bombay’s hybrid street-culture.

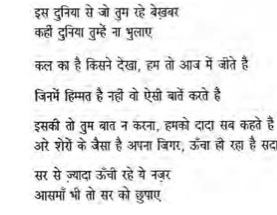

Rangeela: The Ordinariness of Resistance

Rangeela (Carefree) is the story of three characters: Munna, Milli, and Kamal. Munna (played by Aamir Khan), a Bombay tapori who grew up an orphan on the streets, is a carefree but irritable youth who loves Milli (played by Urmila Matondkar), a junior artist11 in the Bombay film industry. One day, Milli lands a big role, and Kamal (played by Jackie Shroff), her costar, falls in love with her. The film weaves in a tale of

The Rebellious Tapori 54

everyday conflict and tension among the three characters, linked pri- marily to the differences in social class and aspirations for a changed life. Munna sees himself becoming increasingly distant from Milli’s world. After a series of twists and turns, Rangeela ends with Milli finally getting together with Munna. This simple story is energized through Munna’s role, performance, and playful resistance to the seductive world of the commodity. By weaving in interesting plot situations, Rangeela seeks to create a series of seemingly superficial conflicts that speak to a larger experience of the city. For Munna, the street serves as his home, his life, and his place of entertainment and is the place where he encounters both the everyday and the spectacular. The street is the stage where a certain freedom enables Munna the chance to perform for his public. Munna’s supposed confidence in the street rests on an absence of inner conflict.12 His per- sonality combines cynicism with audacity, and he retains a sense of humor in his performance. In Rangeela, certain encounters are planned within the narrative that will enable such a performance. These encoun- ters serve to create a conflictual space where the most ordinary and rou- tine aspects of life turn into political performances, like street theater where the actors dialogue with the audience. These encounters produce bitingly sharp, sarcastic dialogues that are meant to convey both the

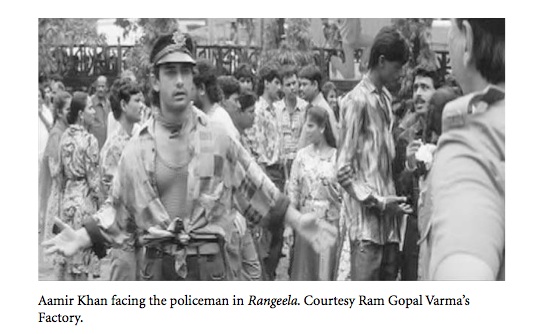

Urmila Matondkar and Aamir Khan in Rangeela (1995). Courtesy Ram Gopal Varma’s Factory. The Rebellious Tapori 55

tapori’s agency and his live relationship to the “public” in the street. Writing on the modernism of Baudelaire and Dostoyevsky, Marshall Berman observes how both writers created a form in which “everyday encounters in the city street” assume an intensity to “express fundamen- tal possibilities and pitfalls, allures and impasses of modern life” (229). While such encounters are common in Hindi films, in Rangeela, these everyday encounters are presented as theatrical events, establishing Munna’s live relationship to the crowd, or the “public.” Munna is first introduced in Rangeela as a black marketer of film tickets at a sold-out show. The sequence begins with a low-angle shot of a film poster featuring a well-known actor. Munna enters the frame wear- ing a hat and smoking a cigarette in an exaggeratedly relaxed style. He pauses in front of the poster for a second and then moves away as the shot changes to reveal the crowd of people waiting outside the movie theater. Munna’s first entry in the film, using a film hoarding (billboard) as a backdrop, again draws attention to the specifically cinematic iconic- ity of the tapori. In the next shot, we see Munna softly muttering “Dus Ka Tees” (30 rupees for a 10-rupee ticket) as he swaggers through the crowd. Munna is trying to sell tickets at a higher price than they are worth. Munna’s friend Pakhiya is doing the same thing. The dialogue, the mise-en-scène, and the performativity in this sequence require some detailed analysis, for these elements introduce the idea of the casual encounter acquiring a larger-than-life, sometimes-political dimension. Munna saunters through the crowd, cigarette in hand, exhibiting confidence. His ticket sale to a man is laced with one-liners, cocky com- ments, and underlying humor. Next, Munna turns to face a policeman. Munna tries to retreat, but the policeman calls him back. The police- man questions Munna about his illegal ticket sales, but Munna denies doing anything illegal. The policeman starts searching Munna, who removes the tickets from his rolled shirt sleeve and tucks them into the fold of the policeman’s cap. Throughout the search, Munna performs loudly for the public. The dialogue is significant here:

56 The Rebellious Tapori

Aamir Khan selling tickets in Rangeela. Courtesy Ram Gopal Varma’s Factory. Amir’s public outburst

Hey brothers, look! The perpetrators of the Bombay riots were never convicted. Millions were embezzled in the stock market. But did they arrest anybody? And me, a simple man who comes to see a film, is harassed! It’s your rule anyway. . . . What will happen to this country yaar [buddy]! (Laughs) This encounter reveals the centrality of performance in the sequence. Munna’s loaferlike clothes are contrasted with the police constable’s uniform. The appeal to the public is made through references to well- known incidents like the Bombay riots of 1992–93 and the share market conspiracy of the early 1990s.13 By contrasting Munna’s petty crime with the larger world of intrigue, violence, and corruption invoked in the dialogue with the public, a certain character development is made. Munna’s style, performance, and posture are presented as a critical strat- egy, while at the same time his charm is introduced to the audience. Actor Aamir Khan says about the tapori: Generally the taporis shown on screen have a very good sense of humor. They do exciting stuff, they are very attractive as characters, so they play to the gallery most of the time. As a result the audiences end up liking them. They speak well, they are funny, their one-liners make you laugh, they have a sense of humor and generally they do crazy things. (inter- viewed in Mazumdar and Jhingan, “The Tapori as Street Rebel,” 1998) The theatricality of the movie-theater sequence in Rangeela resembles the spatial organization of street theater, for which audiences usually sit

Aamir Khan facing the policeman in Rangeela. Courtesy Ram Gopal Varma’s Factory.

all around the performance space. The use of stereotypes and direct vi- sual contrasts also closely resemble the traditions of street theater. The encounter in front of a movie-theater crowd becomes the space for the policeman and Munna to act out a larger world of conflict through an everyday encounter or incident. The tapori’s street encounter, while intro- ducing the character, also establishes his particular appeal to the public, similar to what happens in agit-prop theater. One is reminded here of Brecht’s concept of the social gest. Gest constitutes an ensemble of ges- tures that can evoke the conflicts and contradictions of society (Brecht, 283–84; Barthes 1977, 73–74). Gest becomes social when the interaction or performance is implicated in a larger space of hierarchical conflict, either in the form of a physical gesture or in the twists and turns of lan- guage. By invoking the public during Munna’s humorous encounter against a policeman, the movie-theater sequence appears like a “Brecht- ian tableau,” in which Munna’s playful one-liners are directed both at the people outside the movie theater, in the frame, and at the spectators watching the film, outside the frame. Munna depends on the crowd in the street for his identity. The crowd heightens Munna’s performance and establishes him as different and uncaring of power. Located at the intersection of a range of forces, the human body either submits to the pressures of authority, coercion, and surveillance or cre- ates “spaces of resistance and freedom” (Foucault). This assumption is based on the ways in which power is exercised within organized spaces

58 The Rebellious Tapori

of repression such as the prison, the asylum, and the hospital. But it is possible to have a more creative engagement with the notion of space. Despite the disciplinary formations that govern our existence in the city, it is possible to create alternative (spatial) practices within it. It is through these “tricky and stubborn procedures that elude discipline without be- ing outside the field in which they are exercised” that one can see the formation of a “theory of everyday practices, of lived space, of disquiet- ing familiarity of the city” (de Certeau 1984, 96). De Certeau emphasizes everyday practices through the metaphoric use of the pedestrian’s walk in the city, as the walker assimilates the fragments that make up the everyday world of existence: The walking of passers-by offers a series of turns (tours) and detours that can be compared to “turns of phrase” or “stylistic figures”. There is a rhetoric of walking. The art of “turning” phrases finds an equivalent in an art of composing a path. Like ordinary language, this art implies and combines styles and uses. Style specifies “a linguistic structure that manifests on the symbolic level . . . an individual’s fundamental way of being in the world. (1984, 100) This “fundamental way of being in the world” is articulated through gestures and speech acts that are drawn from fragments selected during the pedestrian’s walk through the city. Confronting a “forest of gestures” that are manifestly present in the streets, the walker exaggerates some aspects of the city while distorting or fragmenting others (de Certeau 1984, 102).

Sanjay Chel has alluded to the experience of intoxication and alien- ation in the city’s life world. For Munna, the glitzy world of glamour, ice-cream parlors, and neon lights stands in sharp contrast to his every- day world, in which even a bus ticket is unaffordable. Located at the crossroads of these contrasting worlds, Munna creates a performative mask, like a veneer that can protect him from the humiliating experi- ence of facing inequality. His desire for the other world or the “good life” exists, but his body acquires gestures and movements that can help him to produce an alternative regime of resistance and autonomy. In this process, Munna’s performance produces a spatial practice of nego- tiating the city, making his presence felt in the densely saturated street. The modern tapori, a creation of the cinematic imagination, articulates in his performance a network of fragmented and fleeting images. Following the encounter with the policeman outside the movie theater,

The Rebellious Tapori 59

Munna walks into a tea stall with his friend Pakhiya. The two friends are established as drifting personalities in the city, with no real commitments or responsibilities. Suddenly Milli walks in. She talks to them about her frustrations at the film set where she works as a dancer. During the con- versation, Munna tells her that his own experience is that of the street, which Milli cannot understand. Milli responds to this in irritation: “The problem with you is that you can’t think beyond the footpath! You should try and get a job somewhere.” Munna replies emphatically in the negative: “Rather than be a dog living on the crumbs of some rich man, I prefer to be on the street, in control of my life.” This exchange is significant and leads up to one of the most important songs of the film (“Yaron Sun Lo Zara”), in which Munna’s “footpath” worldview is pitted against Milli’s desires and aspirations. Munna gathers with his friends as the song becomes the conflictual space where the world of the commodity con- fronts both desire and playful rejection. The song, which becomes a dia- logue between Milli and Munna, is:

Munna: Friends! Just listen a while If you want to live, then live like me! No car, no bungalow, it don’t matter! No money in the bank, it don’t matter! No video or TV, it don’t matter! No suiting or shirting, it don’t matter! Why care for these things Live life, fancy free Milli: Car and bungalow would be great Bank balance would light up our days and nights! Video and TV, Oh what fun! Suiting and shirting, that’s called style! Watch out for these, mend your ways! Munna: Look at us, we are the kings of our will Milli: If the world thought so, it would be fine, but don’t call yourself a king. Munna: Munna Bhai is my name I do what my heart desires Work or no work, doesn’t worry me Who comes and goes in this world, doesn’t bother me Milli: If you’re cut off from this world, What if it forgets you? Munna: Who cares about tomorrow, we live for today. Milli: So speak those who lack courage. Munna: Don’t you say that, I am called the boss With a tiger’s heart, my head stands high Milli: If you try to look above your head Your head will be hidden by the sky

The Rebellious Tapori 61

The dialogue in the song reveals a split in the way Milli and Munna relate to the world of luxury and lifestyle. Though humorous in its rendition and performance, a sense of freedom, rejection, and irony is found here. The song visualizes the impact of commodity display when, in one sec- tion, Munna climbs onto the roof of an expensive car, with his friends heckling the well-dressed car owner. This image appears like a parody of television commercials in which cars are advertised through lifestyle myths of the successful corporate executive. The car glints in the sun- light just as Munna and his shabbily dressed brigade make fun of the lifestyle associated with the car. Munna is opting for a life on the street as a counter to the luxurious world of the commodity. In presenting a counterworld, Munna creates an individualized space, a fantasy world where the rules and surveillance of society do not operate, where the present and the immediate are celebrated, and where Munna is the local dada (colloquial term for “boss”). This is also a gendered space, where the commodity and the figure of woman cohere, and the vantage point of critique is occupied quite conventionally by the male figure. Munna’s emphasis on a “tigerlike” heart and an arrogant stature draws attention to the specifically performative role of resistance in the tapori’s image.

Munna’s performance in Rangeela is charming, but a deep sense of despair informs the narrative. Munna is not an idealistic figure but someone who would like to make his adjustments with the city without losing his sense of pride and dignity. His desire to settle down with Milli

Aamir Khan with his friends in Rangeela. Courtesy Ram Gopal Varma’s Factory.

62 The Rebellious Tapori

seems difficult, given the world she has become a part of. Munna is not drawn to the world of glamour and showbiz, but he tries to compete with that world. This fact is rendered powerfully in a humorous encounter at a fancy five-star hotel, to which Munna invites Milli for dinner. Dressed in a shocking yellow outfit he thinks is presentable for a hotel, Munna arrives in a borrowed taxi to pick up Milli. At the sight of the yellow outfit, Milli bursts into laughter. Munna, however, thinks he is appro- priately dressed for a fancy dinner. The two arrive at the hotel where Munna’s incongruity is exaggerated through his speech and body lan- guage. When the waiter comes to take their order, Munna demands street food that a five-star hotel would never offer. Milli looks shocked and the waiter is dumbfounded. The hotel’s elite space is highlighted by the waiter’s posture and use of language (English), while Munna unself- consciously speaks the Bambayya street language.

This restaurant encounter is laced with humor, and while Munna looks completely out of place, he does not look wretched. Munna’s arrogance and confident posture appear like a performance that can give him access to the pleasures of an elite world without losing his dignity. Munna is positively dejected and hurt only when Milli sees her costar Kamal and rushes off to meet someone with him. Munna’s defeat and hurt in this sequence is given another twist much later in the film, when he chats with Kamal in Milli’s hotel room. Kamal asks Munna about his profession. Munna replies defiantly, “Apun Black Karta Hai” (I sell tickets in the black market). Munna’s posturing with Kamal is directly related to what Aamir Khan calls an “inferiority complex” which the performance is supposed to mask (interviewed in Mazumdar and Jhingan, “The Tapori as Street Rebel” 1998). Munna then sees the necklace that Kamal has presented to Milli. He also sees Milli’s delight at receiving the present. Munna, on the other hand, has a small ring that he wants to present as a marriage proposal. The difference in wealth and personal ability is con- tested by Munna through his arrogant gaze and defiant posturing. These encounters take place in locations of wealth and luxury—the restaurant at the five-star hotel and a suite in another hotel. Munna’s posture and inner conflict in the hotel restaurant and in the hotel room sequences combine the comic with the tragic. This twofold tension im- bues the tapori with a sense of power and freedom—even defeat can be survived with dignity and pride. In a sense, Munna’s performance creates a “form of empowerment which expresses the fact of ‘powerlessness’”

The Rebellious Tapori 63

(Gelder and Thornton, 375). As anxieties about class and sexuality get articulated through a defiant performance, certain expressions are de- ployed to mask this “inferiority” complex. We are again reminded of Chel’s emphasis on the tapori’s defiant gaze. The role of masculine per- formativity is central to the production of this defiant gaze, which be- comes an important element of subcultural politics. This is evident in the way Munna deploys his body. There is, however, a playful approach to masculinity in Rangeela. Specific plot situations are woven into the nar- rative to draw attention to this playfulness, usually through a series of amusing encounters.

Munna is willing to make fun of his physical strength and masculinity in Rangeela. This is highlighted through a drunken conversation between Pakhiya and Munna, which starts with Munna confessing his love for Milli to Pakhiya. Pakhiya does not believe Munna has the guts to tell Milli (tere me daring nahin hai). Pakhiya says he himself had proposed to a woman a while ago and told her he would buy a house and have their children study at a school where the medium of instruction is English. Munna looks at Pakhiya in wonder and asks what happened next. Pakhiya says the woman took off her sandals and hit him! The entire conversa- tion is laced with humorous one-liners in the best tradition of the Bam- bayya language. The conversation is as follows:

Munna: I must say this to Milli. Pakhiya: You will say it? What will you say? You don’t have the guts [the word used in the conversation is daring] to express your feelings.

Munna: Hell! Why raise the same issue. You will understand if you’re in my place. 64 The Rebellious Tapori

Pakhiya: Oh, I know! Say you don’t have the guts. Munna: As if you have guts! Pakhiya: You know what happened two days ago? That fruit seller’s woman, Meena. Munna: Who, Deccan Queen? Pakhiya: Yes, that woman! Day before yesterday, she walked by Gautam street. I stopped her, took her to my room, and proposed to her. I told her that I would buy a house and our children would study at an English medium school. Munna: You proposed! Pakhiya: Yes, I did! Munna: What happened then? Pakhiya: She hit me with her sandals. Munna: She hit you with sandals and you want me to be gutsy? Pakhiya: But, boss, you must admit I have guts. I’m not wimpy like you. Munna: If you go on like this, very soon you will have to open a shop for women’s sandals! Pakhiya and Munna’s conversation reveals a small world of quotidian dreams and desires. Masculinity here is a combination of innocence and machismo, vulnerability and street-smartness. These characteristics of the tapori’s personality are appealing, as they celebrate an ordinari- ness of existence in the world. Pakhiya wants a little home with children who are educated at elite English medium schools. Pakhiya’s little dream is virtually unrealizable. Rangeela does not present the tapori in a heroic struggle against a larger-than-life force, but rather destabilizes conven- tional approaches toward both heroism and masculinity. In this sense, Rangeela remains one of the most interesting of the tapori films. Rangeela’s guiding myth is the space of the “footpath,” which Munna invokes to legitimize his worldview. It is also the space Pakhiya refers to when he shouts at Milli for not understanding Munna. A youthful spirit, quotidian dreams, and desires within a changing urban context mark the tapori’s identity in Rangeela. Mediating the encounters of daily life, Rangeela does not try to project a sense of spectacular vision or direction; rather, mundane stories are strung together to foreground the tapori’s embeddedness within the cultures of contemporary urban life. Munna’s ordinariness is ultimately his most appealing quality.

The Rebellious Tapori 65

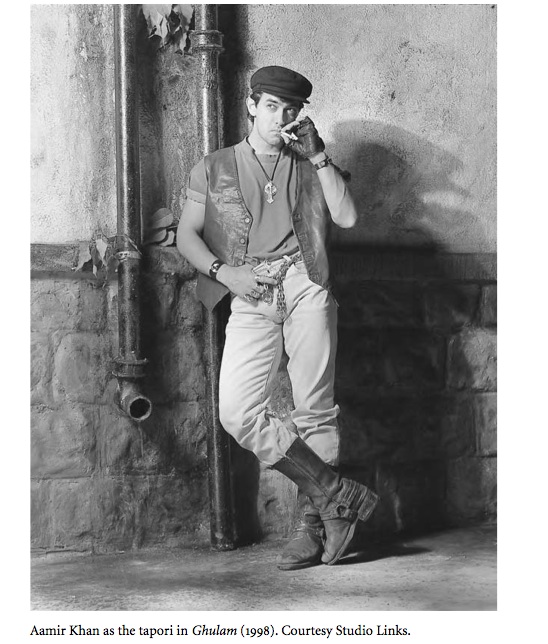

Ghulam: The Tapori as Street Rebel

An adaptation of Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront, Ghulam is the story of Sidhu (played by Aamir Khan), a petty criminal who rebels against the basti’s (poor neighborhood) local don, Ronnie. Sidhu has been bailed out several times by a young female Muslim lawyer, Fatima (played by Mita Vashisht), who has faith that someday Sidhu will renounce the world of crime. Sidhu’s brother Jai (played by Rajat Kapoor) works for Ronnie, helping him collect extortion money from neighborhood resi- dents. Jai is the educated member of Ronnie’s gang, and his computer abilities allow him a special status with Ronnie, who is about to become a powerful builder. Ghulam builds on the relationship between the two orphan brothers with a deeply traumatic past. While Jai rejects his past by keeping its memory alive, Sidhu represses his memory and has a com- plicated relationship to the past. Sidhu falls in love with a girl, Alisha (played by Rani Mukherjee), whose brother works as a social worker in the neighborhood. Sidhu unknow- ingly allows himself to become part of a conspiracy, planned by Jai and Ronnie, to kill Alisha’s brother. The murder is the turning point in the film and creates a wedge between Sidhu and Jai. Alisha’s brother’s ideal- ism strikes a chord in Sidhu’s memory, bringing the past back into his life. The story of the two brothers is situated in an urban context of crime and the illegal operations of builders. This context is grafted onto the city of Bombay through innovative sequences that highlight the spatial contrasts navigated by the tapori, providing the film with a con- temporary ambience. In the course of the film, we learn that Sidhu and Jai grew up on their own after witnessing their father’s suicide, following a confronta- tion between their father and Shyam Sunder, their father’s comrade from the freedom struggle, who accused their father of having betrayed five of their comrades. This confrontation is revealed much later in the film in the form of a flashback. It is an incident that is both present and repressed in Sidhu’s memory. This significant appropriation and repres- sion of the past is important for Sidhu’s identity as a tapori in the city. The narrative fragments the incident by providing us with expressionistic and impressionistic visuals of the father at home, in happy situations, and in flames, falling off the edge of a terrace. The projection of the sui- cide as a fragmented part of Sidhu’s memory is highlighted in the way

66 The Rebellious Tapori Aamir Khan as the tapori in Ghulam (1998). Courtesy Studio Links. the incident is shot. There is rapid cutting between fire, twisting feet, close-up shots of eyeglasses, and sugar falling to the ground. These images are woven together by the sound of a tortured scream. This sequence is repeatedly shown as an enigmatic aspect of Sidhu’s memory. The entire confrontation between the father and Sunder and the en- suing suicide come together at a pivotal moment that will enable Sidhu a second chance to redeem both himself and his father. Ghulam’s narra- tive seems to suggest that Sidhu’s aimless loitering in the city as a tapori

The Rebellious Tapori 67

is possible through a repression of his past. Once his memory returns, Sidhu takes on a heroic persona, elevating the tapori to a new level. Anjum Rajabali, who wrote Ghulam, brought his own perceptions and experiences to the script. Reacting to the rising tide of jingoistic patriotism in several films made in the 1990s, Rajabali consciously chose to evoke in Ghulam a jagged history of the national movement. The past is the site of weakness and betrayal. The father (played by Dalip Tahil) is unable to live up to the expectations of the nationalists. In betraying his comrades, he appears cowardly. But he lives with the memory of the past, and his guilt makes him instill a sense of idealism in his children. This is what Sidhu holds on to. Moving away from uncritical and heroic representations of nationalism, Rajabali destabilized the established norms within which nationalist history had been portrayed within popu- lar Indian cinema. By foregrounding the contradictions and conflicts of the past, history’s relationship to memory and everyday life is established for a new kind of intervention in the present.14 The use of the historical past as a haunting memory for the protagonists gives Ghulam an un- usual texture as the city of contemporary Bombay becomes the stage for working out past conflicts.

Ghulam presents Bombay as a series of compressed spaces, visually exploring the proximity of rich and poor neighborhoods. Sidhu is intro- duced as a man who harbors dreams of the “good life,” precisely because it is inaccessible to him. Like Rangeela, Ghulam develops a conscious strategy of using performance to foreground inaccessibility without making it tragic. City life is introduced in the film first through a series of fragmented shots woven into a song sequence in which performance goes hand in hand with the spatial unraveling of the city. The sequence is rendered through a combination of panoramic and fragmented shots that introduce us to various aspects of city life—shopping arcades, weddings, lovers on the beach, snack vendors in the middle of traffic, and a discotheque. Sidhu and his gang move through these different spaces, dancing in a disco, trying on clothes at a department store, heck- ling lovers at the beach, and gate-crashing a wedding party.

Just before the song begins, Sidhu wields a knife at a man in a car and steals his leather jacket. Sidhu ridicules the English speech of the car owner and the Western music playing on the stereo. However, both the leather jacket and the pizza ordered by the car owner fascinate Sidhu, who appears wearing the stolen jacket several times in the film. The

68 The Rebellious Tapori

jacket functions as a sign of the “good life,” a prop that the tapori is fond of, drawing attention to the circulation of signs. In a discussion of Marlon Brando’s persona in On the Waterfront (1954), James Naremore elaborates on the importance of the short jacket for Brando. The jacket, says Naremore, is not only symbolic of James Dean’s red windbreaker in Rebel without a Cause (1955), but is also evocative of a fragile masculinity that alternates between vulnerability and a rough persona (1990, 206). The intertextual current of the jacket as a sign of “existential rebellious- ness” also makes it a fetish object, enabling the projection of a style in which display becomes “the most self-absorbing feature of a subculture” (Gelder 1997, 374). Ken Gelder draws particular attention to the diffused spaces such subcultural forms may enter, like the spaces of commodi- fication and fashion (Gelder and Thornton, 374). While Gelder’s anxiety is well placed, it is precisely this ambivalent terrain of appropriation and rejection that makes the tapori a significant icon of the cinematic city. In many ways, lifestyle mythology linked to globalization is both rejected and selectively appropriated in Ghulam. The entire aforementioned song is produced through a stylized move- ment of both spatial transitions and rhythmic editing. For instance, when the friends try on outfits at a department store, the scene is edited in fast motion. Comic gestures and gags become part of the performance. Each man emerges from the dressing room to pose before the camera. The last to emerge is Sidhu, who comes out dressed like Zorro. Sidhu shows off his clothing with a mimicked galloping movement. This little performance again draws attention to the intertextual and performative ensemble of the tapori. The irreverence of the song, which suggests a playful and blasé approach to life, is highlighted in the mens’ energized body movements, particularly Sidhu’s. An occasional wriggle of the hips, a backward glance, a pose before the camera, a leather jacket, and a playful masculinity are all on display. With Bombay as the backdrop, the young men are presented as unemployed youth involved in petty crime. When the gang is seen dancing at a disco, one of them picks the pockets of the dancers. The easy movement from one space to the other is remarkable. Sidhu’s gang is comfortable with this diverse spatial land- scape of the city. Later in the film, when Sidhu drops Alisha at her home, the camera tilts up to reveal her skyscraper apartment. At the sense of wonder on Sidhu’s face, Alisha says, “Top floor, flat 22.” This reference to a space in

The Rebellious Tapori 69

the building situates her in terms of both class and power. The entrance- way to Alisha’s apartment is dramatized by low-key lighting, low-angle shots, and slow-motion movement. She walks through the apartment, revealing a large, posh, and excessively expensive home. This is followed by a romantic song, as Alisha imagines herself with Sidhu in scenic natu- ral landscapes. The incursion into this fantasyland comes to an end when Alisha, now back from her reverie, walks to her window and sees Sidhu climbing the water pipe that runs from the ground to the terrace of the building. Shocked at the risk he is taking, Alisha starts screaming, begging him to wait until she gets a rope. Undeterred, Sidhu keeps mov- ing. The camera is deployed to highlight both the risk Sidhu is taking and the spatial location of Alisha’s apartment. Top-angle shots show cars down below on the road that appear like a line of tiny toy cars. The elite space of the apartment is cinematically enhanced through angular shots of the distant street below, captured from the privileged point of view of the high-rise building. This is constantly contrasted with Sidhu on the pipe, trying to reach the apartment. He finally makes it to Alisha’s room and tells her that he was forced to use the pipe because the door- man would not allow him official entry to the building. Sidhu wanted to collect his jacket from Alisha, but his tapori appearance marked him as an outsider to this skyscraper. Class differences and the inaccessibility of elite spaces are highlighted here through a humorous incident that deploys a combination of dazzling aerial views with Sidhu’s risky and foolhardy journey up the pipe. Alisha cannot get over Sidhu’s madness. Sidhu casually wanders about Alisha’s room, which is scattered with cut-glass bottles, a luxury bed, designer mirrors, and posters on the walls. The mise-en-scène plays on the seductive appeal of glass and light, as diffused lamplights are used to make the objects look pretty, expensive, and appealing. Objects in Alisha’s room evoke the lifestyle mythology of the rich. Looking at objects in wonder, but not entirely uncomfortable, Sidhu compliments Alisha on her home. Suddenly, the doorbell rings, and Alisha goes into the living room as her father comes in with a woman. Both are drunk. Sidhu walks into the living room and witnesses a fight between Alisha and her father. When the father sees Sidhu, he demands an explanation. In the heated encounter, he slaps Alisha. Alisha charges out to the terrace in tears. Sidhu walks up to her and says, “Every time I walk by these high-rise buildings, I see the staircase, the windows with their velvet curtains, and the glinting

70 The Rebellious Tapori

lights. I envy the rich who live in these apartments for their wealth and happiness. But today I have seen what lies beyond the façade.” Sidhu’s encounter in Alisha’s apartment is reminiscent of the five-star- hotel lobby sequence in Rangeela. Alisha’s penthouse symbolizes the lifestyle myth of Bombay. Sidhu’s entry using the water pipe shows both the inaccessibility of the place and its distance from the street. Like Munna in Rangeela, Sidhu displays a fascination for elite spaces, but does not lose his street arrogance or performativity. Immediately following Sidhu’s encounters in Alisha’s apartment, the persistence of performance is highlighted through the film’s most popu- lar song, “Ati Kya Khandala”(Will you come to Khandala). By showcasing the tapori’s body gestures during the song, Ghulam attempts to create an alternative spatial landscape of gestures. Despite Alisha’s father’s rude comments about Sidhu’s loaferlike appearance, Sidhu retains his dignity through his subsequent performance. The song is staged at an empty stadium. Sidhu’s solo performance, with Alisha as his spectator, is laced with sharp, cutting lines. Sidhu’s body discourse and performance reject conventional forms of propriety, to foreground a unique language of

Rani Mukherjee and Aamir Khan in Ghulam. Courtesy Studio Links.

The Rebellious Tapori 71

Publicity still for Ghulam. Courtesy Studio Links. survival. The performance combines tricks of the street with the playful use of a red kerchief. The empty stadium becomes a stage for Sidhu’s verbal and gestural performance and for the development of his romance with Alisha. The Bambayya language used in the song becomes a dialogue between Sidhu and Alisha, with Sidhu inviting Alisha to join him on a holiday in Khandala. Sidhu’s swagger, arrogance, and body language are 72 The Rebellious Tapori all on display. As in Narayan Surve’s poem on Bombay, the “loafer” en- counters “two separate worlds,” or spaces of the city, and like a member of the city’s teeming crowd, his movements remain aimless, but his per- formative stance provides the necessary strategy for survival. Ghulam also consciously evokes particularly male anxieties of class and sexuality, explicitly evident in Sidhu’s fascination with boxing. Early on in the film, Sidhu runs into a gang of youth on their bikes in the street. A fight breaks out, but is interrupted by the arrival of the police. Sidhu agrees to meet the gang later at a place called the Sangpara Station, to settle the unfinished fight. The Sangpara Station becomes the site for an unusual duel between two gangs. Charlie (played by Deepak Tijori) and his gang arrive on their bikes. Sidhu is waiting there with his friends. Sidhu and Charlie, leaders of their respective gangs, have to compete against each other. They have to race toward an incoming train and jump off the tracks near a flag on the left side of the tracks. Sidhu’s friends are hesitant about the act, but Sidhu spots Alisha (who at this point is a member of Charlie’s gang) looking at him from behind Char- lie’s shoulder. There is a relay of silent looks here as the performance of masculinity for the gaze of the woman, the real spectator for this event, becomes important. Sidhu agrees to run toward the train, an act that is visually rendered through a combination of speed, sexual energy, the mystical hue of the night, and the decrepit state of the rail tracks. Perfor- mance is central to the identity of all the people gathered at Sangpara Station. Sidhu successfully makes it to the flag in a dramatically shot sequence that creates a montage of the wheels of the train, Sidhu’s run- ning feet, the tracks, Alisha’s tense expression, and angular shots of the speeding train. Charged with a heightened energy, the sequence com- bines adventure with sexual power. The fascination with the train be- comes the medium through which other anxieties are worked out. In the Sangpara Station sequence, the anxieties of class, sexuality, deviance, adventure, masculinity, and illegality are woven into the per- formance. Sidhu not only makes it to the destined spot before the train, but also risks his own life to save Charlie’s, when Charlie falls on the tracks while running toward the marked spot. That everyone in this group is part of a defiant space is obvious. There is a visual ensemble of signs used here. The noise of the bikes, the flashy leather jackets, the knuckle-dusters, and the hooting of the gang are all woven into this

The Rebellious Tapori 73

intensely charged moment. Emerging as a subculture within the city of Bombay, the youth display their own codes, which mark them as differ- ent, drawing attention to the economy of gestures and style that are cen- tral to subcultures. Subcultural performance relies on a set of codes and practices that mark groups as different. The station sequence recalls the analysis of deviant youth cultures defined by Dick Hebdige. For Hebdige, it is important to remember that while the politics of youth culture is “a politics of gesture, symbol and metaphor . . . subculture forms emerge at the interface between sur- veillance and evasion of surveillance” (cited in Gelder and Thornton, 403). The evasion of surveillance that marks the space of both the gangs at the station alludes to another aspect of subcultural politics—the revival of community and solidarity within a new imagination of the street. Therefore, Charlie’s gang, indebted to Sidhu, reappears close to the end of the film to return the favor to Sidhu when his life is in dan- ger. These elements of competitiveness, solidarity, youthful exuberance, and spectacular performance make the subcultural politics of Ghulam an interesting space for the tapori. The Sangpara Station scene at once recalls West Side Story (1961) and Mere Apne (1971), as themes of male aggression, frustration, and anxiety are woven into a minor event. Taking the context of Bombay’s linguistic and cultural hybridity amidst a compressed landscape of architectural chaos, Ghulam presents the urban crowd not as an abstract force but as a multicultural presence. The crowd is marked by cameo figures, whose dress, speech, and role in the film become significant. The regional and religious identities of several figures in the film are foregrounded. There is Fatima, the Mus- lim lawyer, who plays an important role in Sidhu’s life. Then we have a Tamilian vegetable vendor, and a crippled Muslim man from the north- ern state of Uttar Pradesh (U.P.). These characters participate in a local meeting to discuss the violence in the neighborhood. Sidhu himself is presented at the meeting as a Maharashtrian identified by his last name (Marathe). The presence of the crowd and urban chaos are relationally structured around the idea of “empty space.” By contrasting “real” space (the space of the crowd, the street, and the home) with fetishized “empty space,” Ghulam creates a conflictual movement between the space of the everyday and “empty space.” This is most vividly imagined in what I refer to as the ghat sequence.

74 The Rebellious Tapori

Sidhu and his brother Jai meet for conversation twice at a ghat (steps on the banks of river) that is difficult to establish in terms of locale. This space of the ghat is invested with deep emotion. The enclosed walls are bathed in a light-and-shadow pattern reflecting the water at the base of the ghat. The use of the ghat as a meeting point for the two brothers is deployed to trigger a series of associations linked to the contours of the cinematic city. It would be useful here to refer to the well-known taxicab sequence in On the Waterfront as the obvious pretext for the ghat sequence in Ghu- lam. The taxicab sequence, now legendary for its emotional texture and quality of performance, presented two brothers, Terry Malloy (played by Marlon Brando) and Charlie (played by Rod Steiger), inside the space of a cab in conversation about their deep-rooted conflicts. Malloy’s childhood memories are woven into his resentful attitude toward his older brother. In the film, the conversation and the nature of the per- formance dominate the texture of the image (Naremore 1990). In Ghu- lam, however, a similar conversation is located in a stylized space, where the spatial dimension becomes equally important for the sequence to make connections with films like Deewar (discussed in chapter 1). While the “empty space” of the ghat draws attention to the memorable debate between Vijay and Ravi under the bridge in Deewar, Ghulam redeploys the Deewar debate for a different set of ethical dilemmas. The difference is that the conflict between the state and the outlaw central to the nar- rative of Deewar is replaced in Ghulam by an ethical conflict between two brothers, both of whom operate outside the law. What is particu- larly striking here is that the uneducated, rough, street hood questions the educated, urbane brother. Henri Lefebvre has suggested that to understand the importance and politics of lived space, it is important to make connections between “elab- orate representations of space on the one hand and representational spaces (along with their underpinnings) on the other” (1991, 230). This can then explain a subject “in whom lived, perceived and conceived (known) come together within a spatial practice” (230). This philosophi- cal underpinning that guides Lefebvre’s understanding of spatial subjec- tivity provides us with a remarkable entry into the spatial metaphors and symbolic politics deployed by the ghat sequence in Ghulam. It is from the realm of “empty space” that Ghulam moves into the intertextual

The Rebellious Tapori 75

space of other antiheroes, like the “angry man.” Having erased the present and the immediate from this space, the two brothers acquire mythical powers through their confrontation. As familial bonds are put to the test, this “empty space” allows for a complex exploration of morality and justice, a space where memory is evoked and issues of normative action in the face of evil are settled. Jai wants Sidhu to withdraw as a witness against Ronnie. Sidhu not only refuses, but asks his brother why he did not stop him from entering a world of crime. This reversal of Deewar’s narrative through an intertextual allusion makes the “empty” space of Ghulam significant, allowing the tapori the possibility of using his street language as the medium for an empowered critique of the system.15 In Ghulam, time folds back on itself to invest the present with images of the cinematic past (Deewar). This intertextual current of the persistent with the new produces a typical spatial experience of the city, “a particularly acute experience of disconnection and abstraction” (Terdiman, 37). While the allusion to Deewar allows Sidhu entry into a heroic space of conflict, the final fight in the street creates a contemporary, everyday backdrop for Sidhu to specifically address the experience of Bombay. Sidhu’s journey climaxes in a fight sequence with Ronnie as the anxious and expectant crowd watches. Before the fight, the entire basti looks abandoned; the shutters of shops and apartment windows are down. Sidhu walks through the empty basti to his apartment and discovers his belongings on the street. Enraged, he walks to Ronnie’s office and challenges him to a fight. The subsequent fight takes place at the center of the basti, with the crowd reappearing as spectators. All the cameo figures are now present in the crowd (Fatima, the lawyer; the Tamilian vegetable vendor; the crippled Muslim figure). After defeating Ronnie in an extended fistfight, Sidhu swaggers to a shop. As Sidhu opens the shop’s shutter with a brisk movement, the narrative implicitly and sym- bolically presents a critique of what has become a recurring problem of the Bombay bandh (closure). One of the peculiarities of Bombay in recent years has been the Bom- bay bandh, which is usually instituted by the Hindu fundamentalist Shiv Sena Party.16 The bandh is used to shut down shops and transporta- tion in the city as a form of protest that has become associated with the violent politics of the Shiv Sena. This strategy was an ironic reversal of general strike tactics used by the radical labor movement up until the

76 The Rebellious Tapori

early 1980s. The bandh is essentially an urban form of political protest in India that surfaced during World War II, in the last phase of the anti- colonial struggle. The objective of the bandh was to symbolically immo- bilize the movement of the military and the police by invoking the co- operation of public transport workers and drivers of private vehicles in order to bring the city to a halt. In the post-independence period, the bandh was perfected by left-wing parties to symbolize their disillusion- ment with governments in power, at both the regional and national levels. In the 1990s, however, the bandh was often used by Hindu chau- vinist groups like the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Shiv Sena to coerce and dominate. Shiv Sena tactics focused more on street intimi- dation of small shop owners and the institutionalization of an elaborate extortion racket in the street run by local party operatives. By evoking the bandh as a coercive experience, Ghulam imbues the film’s narrative with contemporary events of the city while implicitly critiquing the Shiv Sena’s role in street intimidation.

Anjum Rajabali recalls how as a Muslim he was having difficulty find- ing an apartment in Bombay after the 1993 blasts.17 The frustration from this experience within the larger context of a changing city where Hindu fundamentalism was becoming more and more ubiquitous pushed Rajabali to address these concerns in Ghulam. The reference to Shiv Sena politics, the use of cameo figures who become representative of some kind of urban community, and the desire to reclaim the city became essential markers in the script as the film evolved into a textured archive of Bombay. As the crowd celebrates Sidhu’s victory over Ronnie and the subsequent opening of the shops, Sidhu suddenly spots a cracked picture of his father. The inspiration to rebel and win is there in the image of the father. While the father may have betrayed his comrades under pressure, he had tried to be an inspirational presence for the chil- dren. In an earlier section of the film, the confrontation between Shyam Sundar and Sidhu’s father comes back to Sidhu in flashback. As the fragmented memory takes the shape of a complete picture, Sidhu says to himself, “My father was not evil, he was just weak.” By redeeming both himself and his father, the tapori in Ghulam emerges as the street rebel. Ghulam combines the performance of the tapori in the street with a heroic spirit derived from other vigilante films, in which memory be- comes central to the journey of the hero. While in Rangeela the tapori remains wedded to an ordinariness of survival and being in the world,

The Rebellious Tapori 77